Noah Thompson

Huon

In the last year of my undergraduate degree in 2018 I began work on a long-form documentary project based in my home state of Tasmania, Australia. The work incorporates my own photography accompanied by academic articles and still and moving image archival re-contextualisation, therefore I was researching on a lot of fronts. The project is inspired by the extensive history of conflict between the polarities of environmentalism and industrial development and their implications for the physical, political and socio-cultural landscapes. I see these conflicts, played out in the major theatres of hydro-electricity schemes, logging and mining, as an extension of the same long running contentions that have coloured Australian history from the time of early colonisation.

The project is titled Huon: the name of a species of conifer that is endemic to Tasmania called Huon Pine or Lagarostrobos franklinii, that only grows in the wettest parts of the state’s South West. The tree is somewhat of an unofficial symbol of the state, celebrated for its unique properties. These include a high oil content which means it is especially resistant to decay, a dead tree can remain submerged in water for hundreds of years and appear as if it fell in a few days earlier, a property that made it of great use to early colonial boat builders. Also its exceptionally slow growth rate in which a tree that is no more than 15cm in diameter may be as old as 500 years old. Due to its valued properties the tree was enthusiastically exploited after the establishment of the Sarah Island Penal colony in 1822, so much so, that by 1879 a parliamentary select committee was established to enquire into the preservation of the species and by 1882 the issuing of licenses to fell Huon Pine were suspended.

I left Tasmania when I was quite young, moving to the Northern Territory with my parents and brother during Australia’s recession of the early 1990s but returned regularly to visit family and friends. Before leaving, and on each returning visit, I remember overhearing sober discussions and drunken arguments about old growth logging in the Florentine and Styx Valleys, corruption of what was then the biggest forestry company, Gunns. These discussions were heightened by proposals to build a pulp mill on the banks of the Tamar River (with questionable environmental requirements and hurdles) near my family’s hometown of Launceston.

My mother recounted a story to me from her early twenties in which she told her father of her desire to “go down and stand in front of the bulldozers” during the campaign to stop the construction of the Gordon-below-the-Franklin Dam in the early 1980s. The Dam that would flood a huge swathe of ancient rainforest that had acquired world heritage status but due to a legal loophole was not recognised by the constitution of Australia and therefore ignored by the Tasmanian government of the time. In retort to her protest my grandfather told my mother: “if you do, I will run over you myself”.

These stories were on my mind while shooting for Huon as I attempted to play on this underlying tension in the state that despite various capitulations, victories and ‘forest peace deals’ seemed to continue to bubble under the surface. At the time I was living in Melbourne and making the work through short visits, and when not in Tasmania to shoot I was conducting further research. I had long known of some instances of verbal harassment and physical altercations between supporters of forestry and those against it, of vandalism by either side of machinery or vehicles, death threats and even guns fired over the head of prominent green politicians. There are numerous well documented cases of these, videos on Youtube, police reports and news articles. However, it was one particular case that I found during this research that surprised me the most and came to form the central and guiding metaphor for the project project.

During the aforementioned campaign to stop the construction of the Gordon-below-the-Franklin Dam in the early 1980s, the issue in Australia was reaching fever-pitch. Over a number of years, thousands of activists had been ferried into the remote area to occupy the land and be arrested, with the aim of impeding the construction and keeping the issue in the media throughout Australia and the world through mass arrests. The issue quickly became a central election issue and a federal Labor government, under the leadership of Bob Hawke, was swept to power – in part thanks to a central promise of stopping the dam's construction. Before the dam could be stopped an Australian High Court submission had to enshrine the world heritage status in the Australian Constitution which would allow the Federal Government to overrule the authority of the Tasmanian State Government. Such a verdict was handed down on the 1st of July 1983, literally, stopping the project in its tracks.

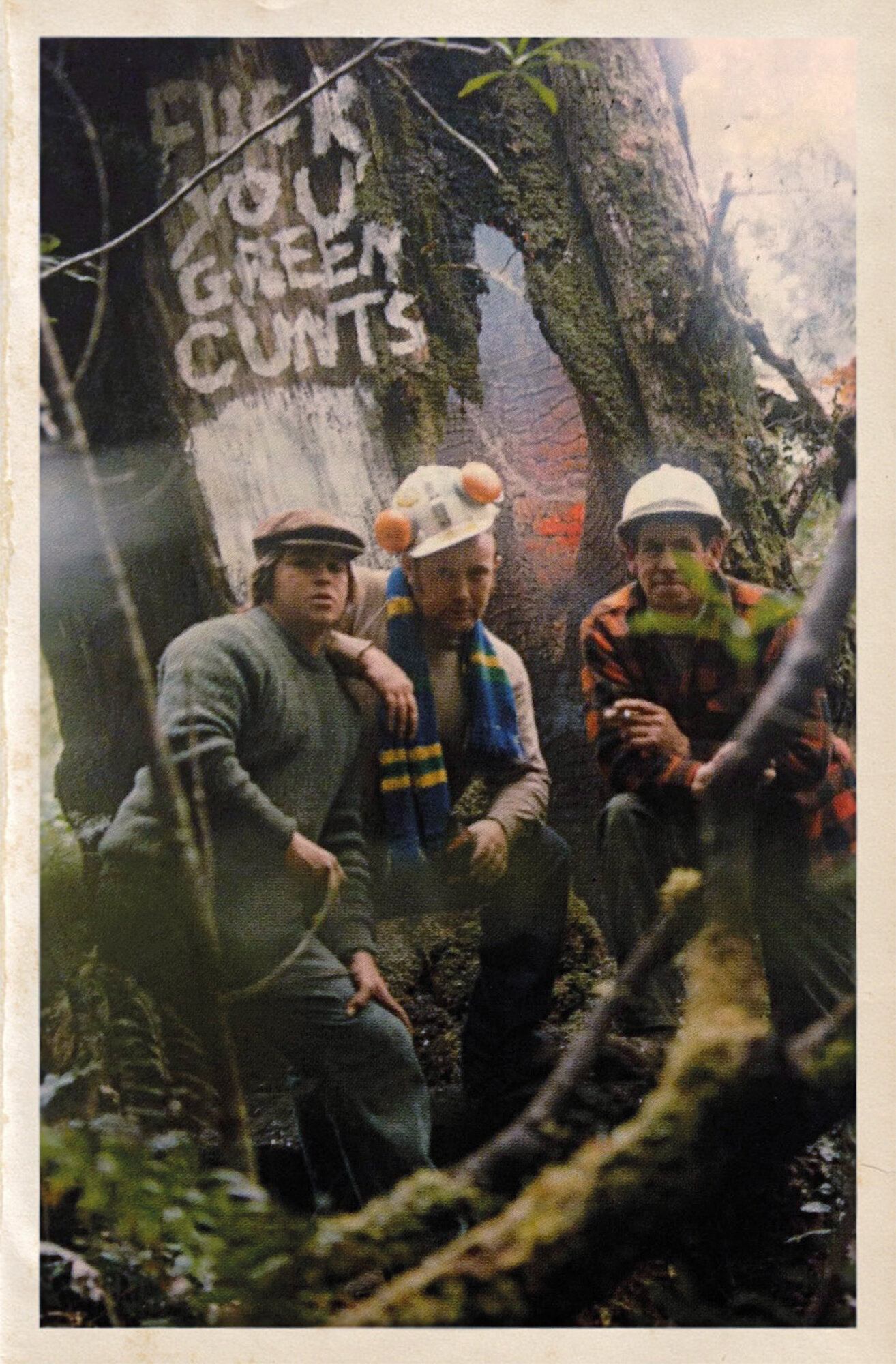

Near Warners Landing, the staging area for the construction of the dam was a Huon Pine tree believed to be somewhere between 2,000 to 3,000 years old. All the more remarkable when you consider the growth rate of this species mentioned earlier. The tree had been left by the convict cutters of the early 1880s as it was too old, too misshapen and it was too large to be moved had it been felled. It was said that three men all over six foot were unable to link arms around the tree. It was significant enough to acquire a nickname, the Lea Tree, and had become a symbol for the conservationists that were trying to protect the area. On the night of the 5th of July 1983, the tree was attacked. It was chain-sawed, holes were drilled in its base to pour oil to its roots and it was set on fire – due to its size it burnt for nearly 24 hours. A message: ‘FUCK YOU GREEN CUNTS’ scrawled on its trunk. Three perpetrators photographed themselves in front of the glowing embers of the tree’s husk, posing as if it were a trophy kill of the hunting of an exotic animal, with the resulting photograph sent to one of the prominent conservation organisations.

I found this story and this photograph online, which I incorporated into an early dummy of my initial photobook but it did not feel as adequate or as resolved as I had hoped it would. I became obsessed with this tree and was convinced that given the hardiness of Huon Pine, that it must still remain in some form. I began to contact various individuals that I had spoken with during the course of the project in an attempt to locate it. I was eventually put in contact with a man who had been there some 40 years previously and had seen the original tree, although he was unsure about its exact whereabouts but after some negotiation he agreed to take me for a fee. The night before our adventure I lay awake in a cheap motel room, adrenaline keeping me from sleep. Of course there was no guarantee we would find the tree or if it even still existed so the eagerness was hinted with a tinge of anxiousness, it was a substantial amount of money I was risking on a hunch.

The next morning, I met my contact, Ron and his off-sider and we set out. Upon reaching Warner’s Landing he observed that the area was quite different to when he had been there the first time he had seen the tree. All the area that had previously been cleared was now covered in young regrowth, with the only defined clearing that of a helicopter pad. South West Tasmania also receives an astonishing amount of rainfall each year, some 2400mm annually, allowing the rainforest to thrive but it leaves the ground boggy and makes progress slow. We trudged about for a few hours, searching for the tree. My guide would disappear from time to time to forge ahead in a certain direction, having grown up in the area he was well accustomed to the conditions and for a man nearing his 70s he was incredibly fit and agile. He returned a number of times with news of other Huon Pines but never of the one we sought. After another hour we headed to the clearing and relative dryness of the helicopter pad for some lunch while my guide reassessed his search efforts. He stood with furrowed brow, eating a sandwich, staring intensely at a non-determined point on the ground, chewing his thoughts.

While he ate and thought I walked around the edge of the clearing of the helicopter pad, having never been in this area of Tasmania before I was intrigued. A slight clearing in a marshy area caught my attention, I thought it would make for some good photographs so I ventured into it slightly. A piece of tape tied to a young tree caught my eye so I headed toward it, once reaching it I caught sight of another and before reaching that I realised I was on a track. I followed this cautiously for ten minutes or so, not wanting to get lost in the thick, wet rainforest as my guide was the only person for hundreds of kilometres. I followed it until I reached an area that had a few large piles of mossy logs, logs that had been felled sometime before and bulldozed into piles. In my excitement I strayed from the path to assess the area, looking about for the Lea Tree, thinking that these logs would signify the edge of the camp that had been and that it must be near. A few minutes later I lost the tape markers and sensing the vulnerability of my situation I stopped, and headed back in the direction I thought I had come from. Eventually I heard the voices of my guide and his off-sider and pushed through the scrub in that direction, emerging at the helipad once more.

My entrance surprised Ron and I mentioned the trail markers I had found, he asked me to show him and he immediately set off following them. I followed behind but he was able to pick up the trail more easily than me and it wasn’t long before he was out of sight. I took my time, wary not to lose the trail as I had last time and this time ventured past the point where I had got lost the first time. The trail reached the edge of a small gully where it descended onto the rainforest floor, it was at this point I heard Ron shouting for me to get my camera. I lost the trail again at this point but followed his voice as we called to one another. I came over a slight crest in the path and there was Ron, standing at the base of what was a very large tree, partially burnt with one side collapsed. The piece that remained intact was possibly some twenty to thirty metres high and appeared to still be alive. It was the Lea tree! On the other side of the tree was a copper plaque, partially singed black from the fire that read” ‘this tree is a living symbol of all trees that now survive because the battle of the Franklin River Wilderness was won on the 1st July 1983’.

I not only found the tree I had sought but a living reminder of the polarities people can be driven to in conflict over what constitutes progress. In addition, it represents a significant chapter in Australian cultural and political history.

Perhaps as an epilogue it is worth mentioning the language used by pro-dam and pro-industry camps in the lead up to this event, the tendency was to paint environmentalists or ‘greenies’ as communists, ‘reds’, hippies and dole-bludgers. The Tasmanian Liberal Premier in one pro-dam protest had donned boxing gloves and was filmed and photographed stating ‘we will fight them’. A not so subtle nod of approval to the violence and intimidation that sometimes boiled to the surface. Another prominent politician of the time stated ‘they should get out amongst the people who work for a living instead of being philosophers or dreamers. ’

If no one is to dream are we to ever improve or simply doomed to repeat the shortcomings of the past?

Based in lutruwita/Tasmania Noah Thompson (b. 1991) is an Australian photographer working with expanded modes of documentary making. Coming from a background in political science and with an interest in visual narratives, his work examines the ways in which individual and community circumstance play out amongst broader social, political and cultural events. With an emphasis on slowness through the use of medium format film cameras, Thompson attempts to delve into the cultural and social subtleties of contemporary Australia while informed by the past.